A while ago I finished the new Zelda game; my 17th completed Zelda title (from a possible 20) is in the books! Tears of the Kingdom was a ludicrously hefty 148-hour journey, and I had to abandon any hope of reaching my traditional Zelda completion percent goals, but there were too many impending game releases in this truly ridiculous year and it simply had to go in the completed pile. So on the pile it is, but that doesn’t mean I’m going to repeat past mistakes and let it float away without writing anything. Now exactly three months after launch, it’s time to delve into some potential spoilers and talk about TotK. Read on at your own risk.

After all the pre-release speculation, it turns out that The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom does a whole lot to differentiate itself from its predecessor Breath of the Wild, even though it also retroactively codifies a new formula from that game’s legacy by following in specific footsteps. We are talking many articles worth of new and surprising stuff, some of which I still probably haven’t seen. But of most interest to this time and place and writer is the clear effort Nintendo has put into re-aligning the open-ended structure of modern Zelda with a handful of elements more traditional to the series – to mixed success.

I wrote a whole month of needlessly granular Zelda countdowns on this site a decade ago, so this pleases me greatly. What say we ignore all the newfangled systems that actually make ToTK great and go straight into critiquing how successfully each of these traditional “pillars” of the series brings back the good times? Some of these BotW barely had at all, and some are just significantly changed-up from the last outing. What do you mean none of this matters?

Dungeons

* 3 / 5 *

Let’s start with the big one. That’s right: after a significantly different take on the concept via Breath of the Wild’s Divine Beasts, Tears of the Kingdom actually brings back some semblance of region-appropriate themed dungeons with delineated puzzle rooms/areas. There are four of these bad boys in total and each one even packs a proper boss – but do they scratch that nostalgic itch the Link’s Awakening remake and Skyward Sword remaster have reminded us we had in the last half-decade?

Well, not really, but they are a massive step up from those Divine Beasts. Not just because the game actually calls them “temples” either (although that absolutely helps); unlike BotW’s tileset-sharing brown mobile puzzle boxes, each dungeon looks meaningfully different from the other three in both colour scheme and layout. Each is also preceded by some form of testing approach sequence that channels Skyward Sword by tying the overworld to the temple via warm-up puzzles and/or fights; this builds the anticipation of reaching the building itself on four pretty successful occasions.

However, for better or worse the open-ended design powering the last two 3D Zelda games persists within the TotK dungeons, no doubt in part by necessity given the sheer power of Link’s new abilities. Each time the player is tasked with the activation of four or five thematically appropriate devices – in any order – to unlock the final boss room. The potential for the truly gnarly labyrinthine conquests we dreamed of as kids is there, but only the Fire Temple really nudges the kind of scale to realise it, and only the Lightning Temple really makes an attempt to integrate the puzzles leading to its mechanical MacGuffins in a way that harkens back to the glory days of Zelda dungeons. Unshackle the Small Keys, Nintendo!

Bosses

* 4 / 5 *

One particularly disappointing element of Breath of the Wild was its de-emphasis on the pageantry of full-on named boss fights in favour of slightly altered humanoid character models. Tears of the Kingdom thoroughly remedies this, in perhaps the clearest return to tradition seen throughout the whole game. Though we disappointingly don’t get to snack on the classic crunch of a good hype-building dungeon miniboss at any point in Tears, when the big title cards come out so do the suitably epic clashes.

Multi-phased, well-scored, and completely distinct from one another, the game’s four temple bosses serve as the central focus of their respective domains in more ways than one. Each is the source of some form of calamitous blight on the geographic region where it resides, ensuring each battle truly feels like a finale – especially in the case of the desert’s Queen Gibdo, which you get to fight twice. What’s more, these boss fights manage to integrate Link’s immense TotK toolkit more successfully than their homes do, displaying clear attack patterns and opportunity windows in that old-school Zelda way but allowing multiple avenues for creative offense at the same time – and you can test that flexibility by fighting them again in the vast Depths beneath Hyrule.

Then there are the overworld bosses, which reach beyond the (returning / remixed) Molduga and palette-swapped Hinoxes of the last game to encompass lumbering, weak-spot-laden Froxes, walking rock fortresses teeming with foot soldiers, hard-as-nails draconic Gleeoks (which get bonus points as returning foes from 1980s Zelda), and the best of the lot: the malleable, always-fun Flux Constructs. Throw in story-tied fights like a nigh-invincible possessed mech, a three-headed volcanic poison dragon, all the manic vehicular carnage of the Master Kohga arena battles and that final boss, and you have a suite worthy of standing alongside anything from prior Zelda titles. It’s just that pesky lack of dungeon minibosses and the irritating framerate-murderer Mucktorok that hold it back from a full score.

Enemies

* 3 / 5 *

We could easily have talked about TotK‘s roster of enemies under a section called “combat”, which of course is its own Zelda pillar, but not enough has mechanically changed there since the last game for me to bother with its own subheading. Instead, let’s look at what you’re fighting when there isn’t a big red bar at the top of the screen.

In terms of bringing proceedings more in line with the classic games, we see the return of Gibdos (in a distinctly ReDead-ish guise), Like-Likes packing new elemental varieties, a horrifying new take on the Wallmaster/Floormaster that morphs into another classic villain upon defeat, even a more traditionally rotund Moblin model now called a “Boss Bokoblin”. Add in the all-new airborne Aerocudas, cave-dwelling glass cannon Horriblins, possessed tree Evermeans, swarming Little Froxes and heirarchy of Zonai Constructs, and you have a game without the enemy variety issues of its older brother.

Unlike with its designated bosses, however, Tears of the Kingdom doesn’t quite match this visual spice to meaningful gameplay variety. With the notable exceptions of the magic-weak Gibdos – best exemplified by that magnificent town defense set piece – and the pattern-bound Like-Likes, every new enemy is essentially just another health bar to deplete. The red Gloom-covered variants in the Depths add more peril to the player’s mistakes, but don’t change much else. So it’s just as well the combat / enemy equation in Tears integrates so well with our next section:

Items

* 4 / 5 *

Though Breath of the Wild built much of its systemic depth on a massive breadth of collectable, consumable items and resources that could interact in intuitive ways, Tears of the Kingdom truly takes things to another level not only in terms of the Zelda series, but triple-A videogames in general. For the sake of comparison simplicity, however, let’s put all those pesky Zonai devices and building materials aside.

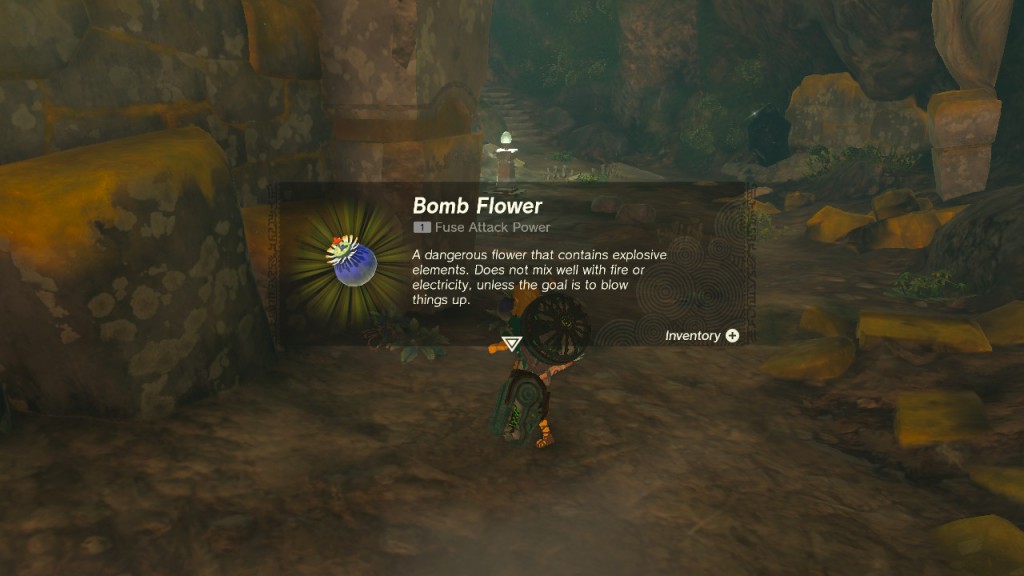

I’ve always been a fan of a good consumable item across the Zelda series – particularly where an in-game economy benefits from the added complexity – and boy does TotK deliver in this area. Everything you pick up has a genuine use, and most have several. Pick up an Ice Fruit (or make your own White Chuchu Jelly in combat) and you have a makeshift arrowhead to freeze enemies, a hand-thrown platform-maker over a body of water, an attack boost cooking ingredient in cold climates, or a modest source of emergency income.

The transformation of every enemy into a source of weapon power (and glamour) is a masterstroke, the discipline of Hylian Pine Cone shenanigans will doubtless be mined for years to come, and the sheer nostalgic mileage derived from making bombs a consumable, semi-rare resource again cannot be understated. Despite all the utility of Link’s inherent abilities in Tears of the Kingdom, it may just have the best itemisation depth in the entire series. The game’s menus can barely keep up.

But there is still no hookshot, so I can’t in good conscience give the game top marks on a page like this.

Companions

* 3 / 5 *

Yes, that underrated and often controversial Zelda pillar only I seem to really care about. I probably wouldn’t bat an eyelid if someone played a hundred hours of Tears without mentally clocking that the game even features companions, because the ghostly avatars of the major sagely players never open their mouths while out and about. They are essentially extensions of Link’s ability set, only with cooldown timers. You can even dismiss them entirely at will.

But I say a character that travels you throughout the game is a companion nonetheless, and there is something to be said for the fact that each new sage adds their powers on top of the others as Link grows in power, to the point that it’s possible to fill the screen with a fully-stacked squad of teal on your march to the finale. It feels narratively satisfying in a way Breath of the Wild’s intersecting red beams couldn’t quite manage.

But there is no doubt that this option can result in some visually messy moments and accidental screenshot photobombs; activating the right sage power in the heat of the moment is also often an exercise in frustration. Then there’s that mute ghost element: though the Zelda series is infamous for needlessly chatty travel buddies, the choice to make these allies shells of themselves robs the story of the character bonding possibilities that lead to emotional moments like the Skyward Sword, Majora’s Mask and Spirit Tracks finales.

Story

* 5 / 5 *

Including this pillar is perhaps a tiny bit cheeky, as Breath of the Wild certainly didn’t go without a story; but no matter how many lore videos you watch there’s no denying that game had its emphasis elsewhere. An obscenely open structure certainly limited its narrative aspirations, and so propulsive plot was a necessary and understandable sacrifice; but as a result the expectation for Tears of the Kingdom to deliver a story with proper meat on its bones was thus quite low – for me, at least. Turns out I absolutely underestimated Hidemaro Fujibayashi’s team on this one.

While it’s hard to see Tears topping anyone’s Zelda narrative list, the difference in ambition and execution over Breath is night and day, and I certainly wouldn’t push back on anyone including it in a series top five. Thanks to a more restrictive tutorial, clear quest tier categorisation, much more careful placement of linear story beats and a devil-may-care abandonment of the fear of confusing players who collect its Tear flashback cutscenes out of order, TotK manages the unthinkable: a coherent, satisfying story by Zelda standards.

The plot certainly has its issues – the main three characters barely interact and this is no return to the early 2010s era when the writers cared about the franchise timeline – but those issues have refreshingly little to do with “open air” game design. Tears of the Kingdom marks a fittingly glorious return for Ganondorf as a menacing force, there are a couple of fun twists, Zelda has more to do than in almost any other story bearing her name, and that chef’s kiss of a finale finds Nintendo at last willing to look at its contemporaries for exactly the right kind of inspiration. It’s good stuff.

We could go into other classic Zelda checkmarks and combarables, such as world design, economy, minigames and side quests, but its probably fair to say Breath of the Wild already maxed these out and its sequel hardly takes a step backward with any of them. But there you have it: 2000 words without really touching on any of the most interesting game design discussion points presented by The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom. Oh well, there will be time for that later. Probably.