Feels like as good a time as any, right?

I struggle to motivate myself to sit down and write anything unless I can link it – however trivially – to something topical or current. But during the mind-numbing malaise of the 2021 lockdowns, I almost posted a Banjo-Tooie-themed article that had no such link. Almost. The half-written retrospective has sat in my drafts folder for years now, but since Nintendo and Microsoft at last decided to release the game on the Nintendo Switch Online Expansion Pack service last week (fittingly two years after Banjo-Kazooie hit the program, mirroring both the original release and story gaps), I have not only a bona fide excuse to replay the game yet again, but to revive, massively expand, and publish that very draft.

It’s been over five years since Banjo and Kazooie were announced as a joint DLC character for Super Smash Bros Ultimate and their trilogy of corresponding games on Xbox received a slew of 4K-enhanced patches. It’s been five days since the game hit NSO. Now, after I revisited Donkey Kong 64 with a critical eye in 2015 and played all of Conker’s Bad Fur Day in one day in 2018, I present to you the next entry in the library of opinionated late-90s Rareware platformer coverage on this site: my unsolicited, recently-refreshed musings on the slightly divisive sequel to the star-making, Jiggy-collecting Banjo-Kazooie.

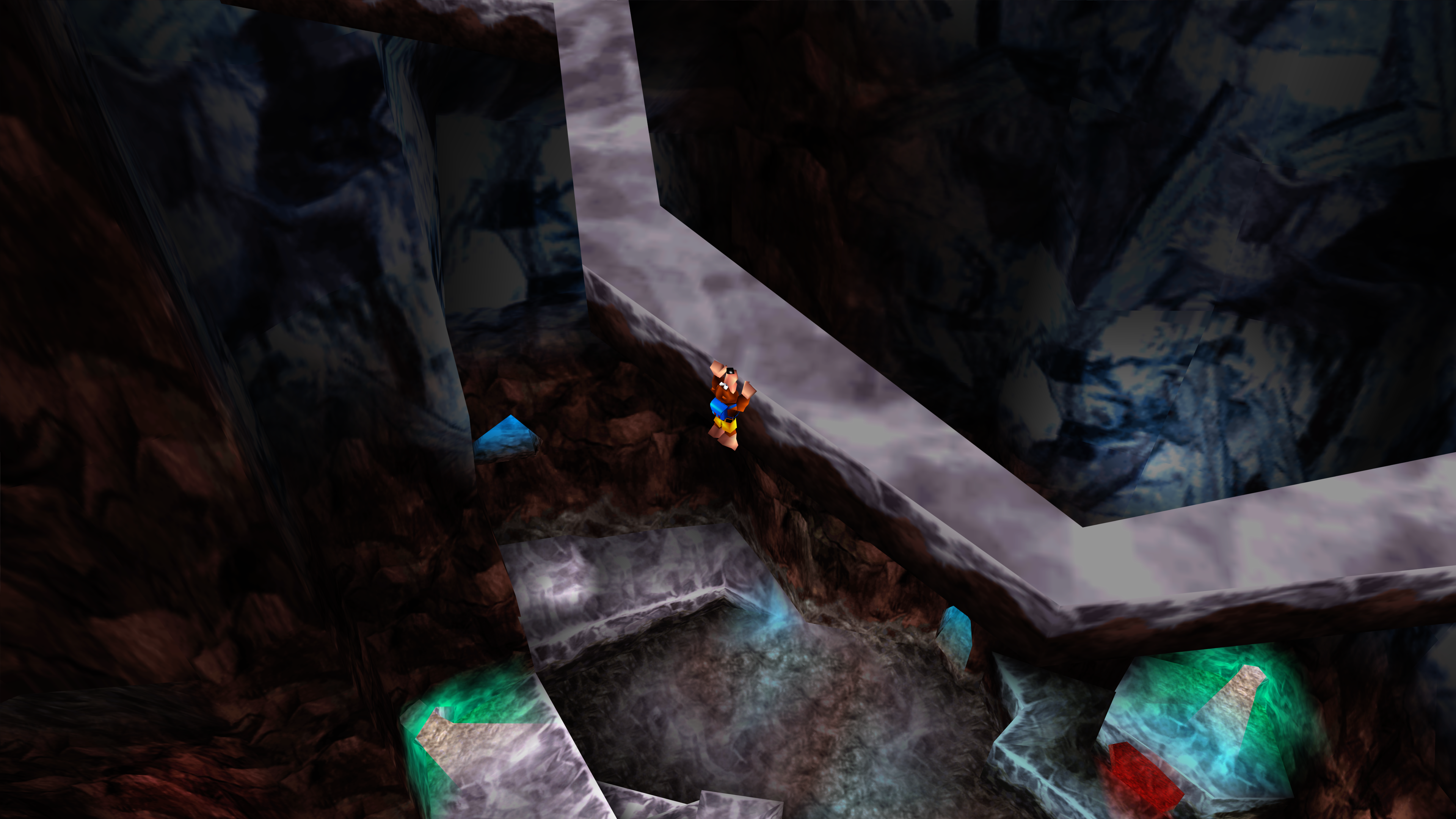

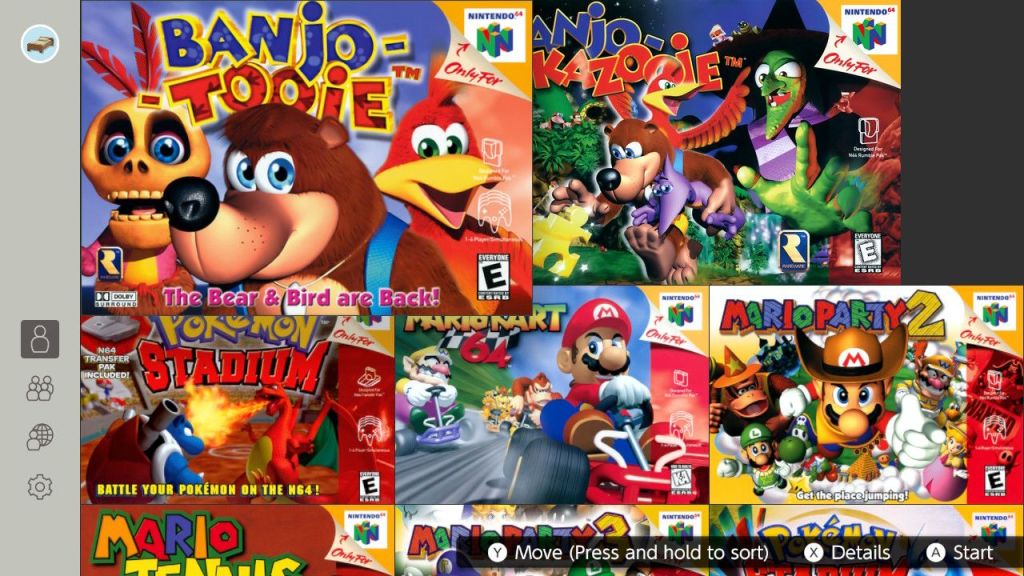

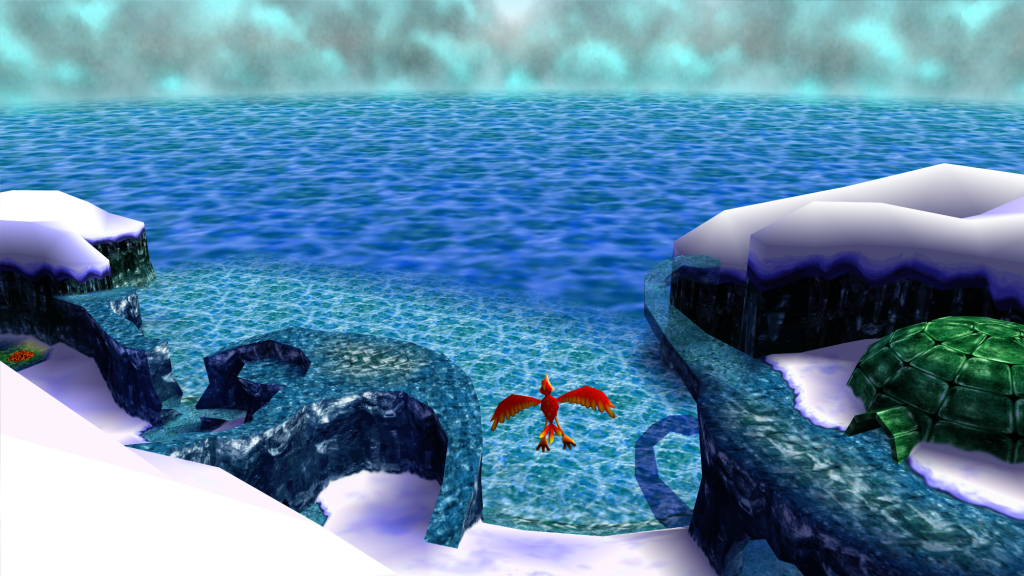

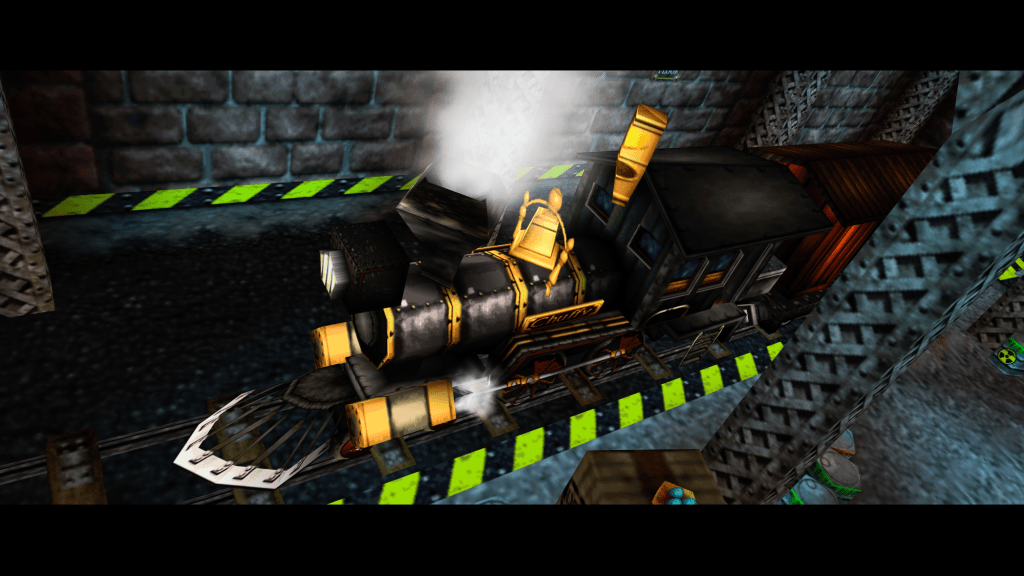

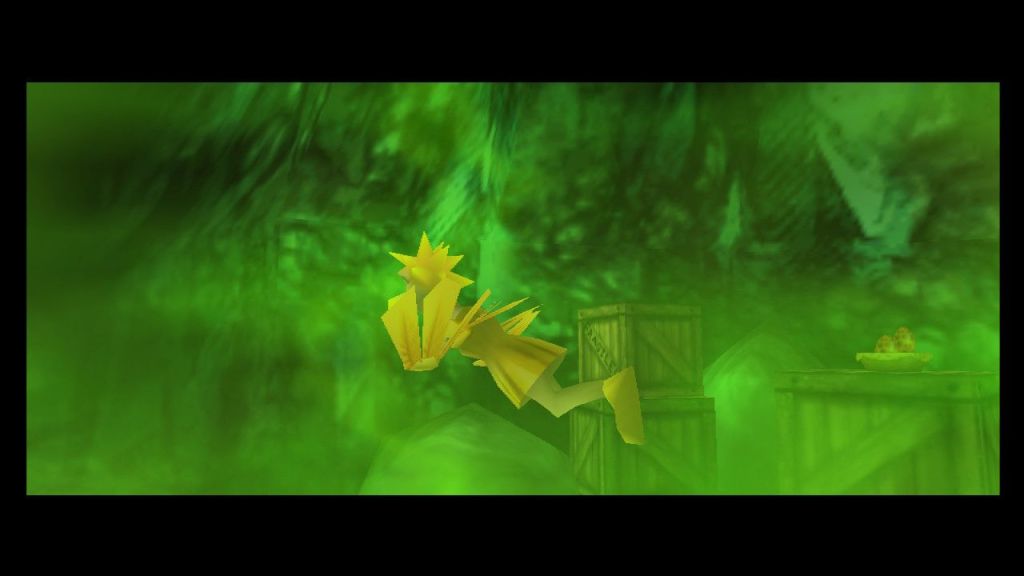

Screenshots from both the Switch and Xbox versions will appear throughout this article; can you tell which is which? There are literally no prizes for guessing correctly!

Long-Buried Treasure

The Xbox version of Banjo-Tooie, first released on Xbox 360 in 2009, made a reasonably big deal about packing a ton of small easy-to-miss updates to the game’s UI, controls, and even rendering. But returning to the original code with a wireless Nintendo 64 controller in hand for the Switch release is somewhat of a shock, because it’s actually pretty indistinguishable at a glance. Did you know that unlike in Kazooie, there was a widescreen mode built into Tooie’s original release, accessed via the rudimentary settings menu on the file select screen? I sure didn’t, and the Switch version even auto-corrects any potential stretching issues to just about fill the whole panel; ergo this is the first game I’ve played on the NSO app that doesn’t have those ugly black-grey gradient panels on either side of the image!

Back in 2001, when the game was released down here in Australia, not only would widescreen TVs be pretty uncommon, but even when rendering the game at the standard 4:3 TV aspect ratio Banjo-Tooie was infamous for running at or below 20 frames a second; adding more screen real estate would have a truly heinous effect on performance. This may be one of the earliest instances of accidental future-proofing present in a 3D videogame, because the much-improved Switch emulator obviously has little issue running the game at 30 frames a second, and those colours absolutely pop on that OLED screen.

Playing in handheld mode without the N64 pad brings up expected control issues the Xbox version was able to solve for the most part years ago, but this is still a far cry from the struggles of navigating DK64 on the Wii U almost a decade ago: everything is still eminently playable. There is, however, one major advantage the original springy control stick still offers that even the famously fantastic Xbox controller design could never quite circumvent: sections of this game were unavoidably designed around analogue control that fights against you when you try to move away from the stick’s default position.

Whether all that many wobbly N64 control sticks had any fight left in them by 2001 is another topic entirely, but Rareware had become masters of bespoke 64-bit development, and Tooie’s movement systems are finely tuned to fit that specific type of resistance. The two early-game trials of tip-toe stealth are almost laughably easy on a reasonably unused N64 controller, but the real advantage arrives whenever you enter first-person egg aiming – which it turns out is awfully often. A reticule that mirrors the physical properties of a N64 controller, constantly returning to centre whenever pressure is removed, just feels so unintuitive on a modern analogue stick.

I remember digging out the Xbox Elite controller I used only for Halo in 2019 just to tighten the resistance on the sticks and tweak movement dead zones in an effort to simulate that snap-back feeling and complete the infuriating UFO mini-game, to absolutely no avail: I couldn’t even qualify for the 400pt “second prize”. This time around? Well it’s still one of the hardest challenges in the game, but I had over 450 on my first attempt, and the very next try cleared the 500pt Jiggy requirement by another 19. Holding the reticule within that mid-stick semicircle is just so much easier.

A Large Undertaking

Aside from those entirely-new aiming mechanics, the number one thing that differentiates Banjo-Tooie from its 1998 predecessor is size. That’s also easily the number one criticism levelled at the game by fans and commentators in the two decades since its launch. You used to hear it online almost as often as the complaint that Donkey Kong 64 has too many collectibles; Banjo-Tooie is just too unnecessarily big. Like other such comparisons that gathered steam online, the narrative can be summed up rather succinctly: Kazooie is tight and well-balanced while Tooie got caught up in the need to feel grander but feels much emptier as a result. While I was cruising through my latest Xbox playthrough of the game – and then this newer Switch one – I tried to keep this criticism in mind, and though it was always fighting against my nostalgic appreciation for everything it does so well, I think I came out the other side with a more balanced take.

While not immediately obvious in the game’s lightning-quick (and weirdly dark) introduction, which simply takes place in the ruins of the first game’s hub world Spiral Mountain, it’s not long into Banjo-Tooie that you notice how much extra space surrounds you; the very presence of instant-transport silos and warp pads betrays as much. It’s not too difficult to understand the appeal of making a game like this to the late-’90s Rareware team. They were quite famously one of the only development teams in the world that seemed capable of getting anything impressive out of the Nintendo 64’s uniquely restrictive hardware – at times giving Nintendo themselves a run for their money. A flex probably seemed perfectly reasonable – expected, even. So a significant percentage of your time in Banjo-Tooie is spent running across open expanses of land – a state of affairs made all the more obvious on the Xbox One X (or Series X), where edges are razor-sharp but textures are massive and muddy.

Just how significant of a problem this is for you will probably come down to the enjoyment you get out of the minute-to-minute building blocks of the gameplay. Even looking out for size problems on these playthroughs, I found I still hardly noticed all the extended space I was covering (most of the time) because these interlocking elements bring me so much fundamental gaming joy. They have always been hard to explain for me, although to be fair I’ve spent most of my life feeling like I didn’t need to. To the best of my ability I can break them down into three key parts:

- The feeling of movement;

- The music and sound design;

- The pull of the player’s next objective.

For me the fun of playing Banjo-Tooie only truly breaks down when one or more of these elements is meaningfully obstructed or broken. When all three are humming along, the scale of Banjo-Tooie‘s large worlds is only ever at worst a mild nuisance. Yes, even in the wide-open plains of Terrydactyland. So let’s explore these building blocks, shall we?

We Move, We Shake

The more action-oriented videogames I play – particularly of the open-world and/or platforming variety – the more I find I appreciate well-crafted, satisfying movement systems. There’s something quite liberating about being able to notice their often-undervalued power, recognising how difficult they are to get right and seeing just how crucial they are to my personal enjoyment of a videogame. I have to say playing Tooie again from a modern perspective starkly illuminates one of the most fundamental design aspects my brain had successfully obscured for decades. Getting around in Banjo-Tooie feels really good, and that makes every part of the game better.

Of course, the game’s movement system is based on an earlier, smaller, aiming-drama-free, more widely-beloved game, Banjo-Kazooie (also available on both Xbox and NSO), which in turn owes a great deal to the pioneering 3D platformer Super Mario 64. Kazooie‘s wonderful mid-jump control and multiple options for both ground and aerial traversal are all present and accounted for in the sequel – a fact that has arguably grown more impressive over decades of second and third games stripping entire movesets from their predecessors. But now there are even more enhancements and bits of tuning to rein in the mistimed pitfalls, and much more variety to keep the A-to-B journey interesting.

At the centre of this design philosophy is the Split Up ability, introduced in Tooie’s third world and gradually enriched with upgrades for the rest of the game. While little more than a novelty that actively de-powers the player at the outset, by the time both Banjo and Kazooie’s individual kits have been fully upgraded, the opportunity to control either one becomes arguably more exciting than the default combined state.

Banjo gets built-in wading boots, the ability to regain health wherever he can afford to stay in one place for a few seconds, and an immensely satisfying double-jump that chains off a powerful airborne attack, Super Mario Odyssey-style; Kazooie becomes straight-up ridiculous, with road-runner ground speed, so much added height on every kind of jump that it feels game-breaking, and the ability to glide across entire levels without expending any resources – all while the game’s entire arsenal of varied egg ammunition remains fully accessible. Her lower health pool isn’t much of a downside; on every Tooie playthrough I’ve ever done there are times I use a standalone Kazooie even when I don’t need to.

The concept of transformations returns from the first game to add even more spice, and this time manifests more consistently than before: each of the eight worlds boasts its own distinct form to inhabit, and all except Hailfire Peaks’ deliberately out-of-place sentient snowball feel powerful and/or indestructible in their own ways. Then there’s the redesigned Mumbo Jumbo, who is now fully controllable; while by necessity his moveset kinda has to be restrictive, the developers crucially gave him a jump with the same potency as Banjo’s, and threw in the most satisfying melee attack in the game for good measure. Locomotion is paramount throughout Banjo-Tooie, and I am not talking about Chuffy the Train. Yet.

Grant the GOAT

Fabled composer Grant Kirkhope’s work during his years at Rareware is well-celebrated to say the least, and his pioneering use of cross-fade in Banjo-Kazooie to sub in different mood variants of the same catchy world theme when the player transitions between interior, exterior and aquatic settings is back smoother than ever in the sequel. We are talking about music here, so of course my nostalgia makes me heavily and unavoidably biased, but I have no notes on this wonderful suite of musical themes: they all reflect an artist on the top of his game, and they rather impressively fit the unique vibes of each environment perfectly without ever really feeling like a lost part of either his Kazooie or Kong soundtracks.

The optimism of the former and the still-odd melancholy of the latter do occasionally weave their way into a Tooie bar or two, but always in moderation; always balanced by a melody that grounds the player in a fitting sense of place. I’ll be honest: I haven’t ever played this game on mute for longer than a couple of minutes; the music (and the general sound mix, come to think of it) are too crucial to the experience for me, and ultimately just another reason why the longer travel time between areas doesn’t usually bother me.

Kirkhope also had to come up with at least one additional variant per world this time around: a boss theme, often enlivened by tense faux-strings and bombastic brass. That’s because much like those transformations, each world now has its own grandiose, Mario-esque boss fight tied to one or more of its collectable Jiggies, and when the player encounters them is likely to vary wildly. This makes these encounters relatively unique among 3D platformer bosses, especially since some require more prior obstacle removal than others.

The inimitably creepy inflatable Mr Patch sits front and centre of Witchyworld, for example, and many of the game’s more complex Jiggies require the defeat of train boiler resident Old King Coal as a minimum prerequisite, but reaching Weldar of Grunty Industries is almost guaranteed to happen late in your exploration of that labyrinth. Perhaps the best instance of this any-moment-now threat comes in the very last world, where Mumbo himself might just be an impostor – and doesn’t that Kirkhope track play some fabulous tricks with your audio familiarity.

Industries, Interconnected, Intertwined

It remains one of the coolest uses of Chekhov’s Game Mechanic I have ever experienced. When you first enter Banjo-Tooie‘s sixth world, Grunty Industries, what you can explore amounts to the exterior of a gargantuan multi-story building mired in polluted sludge. There are nooks and crannies aplenty to explore outdoors, but the front entrance to the building itself remains stubbornly barred by massive shutters. I know I wasn’t alone when on my first playthrough I tried in vain to get in from every possible angle, both figuratively and – for poor Banjo – literally banging my head against the problem until at last it clicked: the switch to open the world’s train station is only outside the building because the game wants you to enter via the game’s railway system.

Said railway system has up to that point only been useful for transporting NPCs between worlds, and – as it turns out – to put an outside-the-box tool into the recesses of your mind so you can recall it for this exact, utterly brilliant moment. But that of course brings us to Banjo-Tooie’s sharpest double-edged sword, and the shakiest of those three pillars I brought up earlier: this game connects its platforming worlds with unprecedented complexity, and stretches out some of your gameplay objectives to near-breaking point. When people talk about the sheer size of Banjo-Tooie as a net negative, this is where I can empathise with them the most.

The immediate draw of your next objective is never far away in the earliest hours of Banjo-Tooie, as Mayahem Temple packs in some relatively dense level design and almost every problem can be solved as soon as you encounter it – even the one that sends you straight to the fifth world via a tunnel leading to one of the aforementioned sneaking sections. You get to sample that world’s theme tune early, everything feels neatly connected, the scope of the game immediately feels large but manageable, it’s all fine and dandy. Unfortunately, the worst level in the entire game is the second one you’re expected to visit.

Glitter Gulch Mine sucks. It’s got a great theme tune, naturally, and like most of Banjo-Tooie’s worlds it avoids cliched, worn-out level themes by attempting something a bit different. However, despite the shiny piles of colourful ore scattered throughout its central caverns, most of the important rooms along the world’s edges are signposted by boring brown tunnels that all look the same, and the winding minecart track you might want to use as a makeshift waypoint frequently takes you through narrow passageways where you cannot see where you are, and if you have the gall to try you have to fight the infamous spectre of the 90s 3D platformer camera. This is why, on every playthrough since my first, I always make sure to collect enough Jiggies in Mayahem Temple to skip GGM and go straight to the superior Witchyworld.

But nonetheless, the mine is a clear early sign from Banjo-Tooie that it does not mind wasting your time, and there will be several more opportunities afterwards for it to remind you of that fact. Especially whenever you are required to transfer directly between levels, the cool worldbuilding implications and clever cognitive foreshadowing is often countered by one too many linked tasks and/or a couple instances of backtracking more than you’d like. In many cases, if you don’t plan your routes through and between worlds efficiently, ideally aiming to knock out more than one objective at a time, that’s when those lengthy trips between landmarks and goals start feeling “too big”. While I find playing that way immensely rewarding, it’s not always easy to do so on a first playthrough.

Luckily, the visual and conceptual imagination on show throughout most of the game is still wholly unique among the genre today. Hailfire Peaks crashes ice and fire biomes into one another with chaotic fun results, Jolly Roger’s Lagoon hides 80% of its mass underwater in a wonderful sucker-punch reveal, Terrydactyland feels like a wide-open playground in its best moments, the regimented floors of Grunty Industries are oh-so-satisfying to claw your way up once you get inside, and the twin threats of Witchyworld and Cloud Cuckooland each throw disconnected, unhinged ideas at the wall to leave the player with memories you’d be hard-pressed to find elsewhere in gaming. The surreal finale of the story lives up to Rare’s high standards, delivering humour and challenge in equal measure with immensely satisfying results. It’s a good game, I tell you.

The Stressful Six

So that’s my main thesis on Banjo-Tooie after all these years, but no discussion on this game can be complete without a nod to the six Jiggies that used to drive me up the wall as a kid: six challenges that were so difficult they each took me days to conquer, and still remain painful in some way to this day. They don’t affect my view of the game as a whole, as Tooie doesn’t reward completionism in quite the same way as Kazooie does, but I always seem to bring them up instinctively whenever I talk about the game with friends, so it feels odd not to include them here. Of all Rare’s collect-a-thon platformers, these are among the company’s most devious roadblocks, and we’ve already talked about one of them: that Saucer of Peril UFO shooting gallery.

The next two make the list for similar aiming-related reasons. The giant anger fish fight in Jolly Roger’s Lagoon is Banjo Tooie’s most infuriating boss, as the swimming controls become rather restrictive in the contained – and often pitch-dark – arena where you’re expected to fire grenade eggs at tiny glowing spots that often end up so close to you by the time you’ve lined them up that you also often cop splash damage. The same world tasks you with another tricky aiming challenge: a linear escort mission of sorts where you must pick off piranhas that swim towards a curious underwater photographer. No matter what vantage point I take up during this shooting sequence, I always seem to see an approaching fish too late to take it out before the timer stops.

Of course, one of the game’s most frustrating Jiggies is found in Glitter Gulch Mine: the world’s trademark disorientation goes up a notch during the “ordnance storage” first person shooter scavenger hunt, and the similarly confusing FPS section in Grunty Industries known as Clinker’s Cavern isn’t much better. But you probably know what takes the number one spot if you’ve ever played Banjo-Tooie: the mother of all tough Jiggies, originally freed in Glitter Gulch Mine and later met in Cloud Cuckooland; the game’s true final boss. The smug bird known as *shudder* Canary Mary races you through the sky with an evil suite of coded comeback mechanics under her belt and truly, deeply tests the patience of any player, of any age.

A Rare Opportunity

If I published this post a decade ago, I’d probably end with something about the community’s hope for a proper platforming “Banjo Three-ie”, as so cheekily teased in Tooie’s final cutscene. The gaming landscape now looks so different that such a hope feels silly, but I’m just glad I finally got to talk about one of my favourite videogames in earnest, with some shred of topicality at last. I may have buried the lead a bit here, but truth be told I’ve always preferred Banjo-Tooie to Banjo-Kazooie despite (perhaps because of) its increased complexity and emphasis on pathfinding over pure platforming. Now the game is out there more accessible than ever, so go give it a try if you’ve ever enjoyed a 3D platformer!