NOTE: This article is itself an updated re-release of one originally posted in 2019. This 2024 version updates all the formatting, refines terminology, adds more examples and hopefully makes some clearer arguments. To read the original (outdated) post, CLICK HERE.

It’s been a topic at the forefront of gaming for at least three console generations: the videogame industry is now old enough to look back and draw from its past, and in an age where some games of yore are ridiculously difficult to experience with anything approaching legality, re-releases distinct from their original source in all manner of ways are as commonplace as they are guaranteed to attract online discontent. In many cases, they also represent a near-guaranteed source of revenue for publishers keen on mining nostalgia, so whether you love them, hate them, or pay them no mind until one of your favourites arrives in the spotlight, they aren’t going anywhere.

What I find most interesting about the modern re-release is that the quality and even validity of a given project oftentimes seems to hinge on what labels people are willing to attach to it. As with most things in life, enjoyment is regularly determined by expectation, and the wrong label can instantly diminish the hard work of thankless development teams, sow confusion over lengthy production cycles, or encourage needlessly circular pricing debates. So I feel like it’s worthwhile to break down and categorise those very labels as I see them defined today.

Because seven is a poetic number that looks great in post headers, that is how I have attempted to divide them – even if I have to stretch a bit to do so. It’s all just one person’s take after a couple of decades following the videogame industry – and I can definitely see people disagreeing on the order of the categories – but I’ve tried to articulate with examples as best I can.

Port

Your basic “Take Game A from Platform B and get it to run on Platform C” situation. Nothing more, nothing less. This is regularly seen when a period of platform exclusivity breaks and a title shows up on a competing one within the same generation. Because timed exclusivity within the console space is a rarity nowadays, the platform that is usually either early or late to the party is the PC, but you see more variety of circumstance the lower down you go on the production budget scale. For every big-budget early access title on the Steam/Epic Games storefront, every surprising eleventh-hour Yakuza/Square RPG arrival, there’s a “Nindie” debuting on Switch first, a small ID@Xbox game flying the Game Pass flag straight out of the gate, a former Apple Arcade exclusive that manages to find an unlikely second life somewhere else. When these games inevitably cross over to find new homes – grabbing a handy second wave of buzz in the process – they invariably do so without significant gameplay changes or extra content that hasn’t already been added to their initial versions.

The overwhelming majority of PC ports do offer more flexible graphical options due to the open nature of the PC environment (usually related to resolution, frame rate caps/unlocks, and previously unavailable visual effect toggles), just as a huge amount of Switch ports require technical downgrades by very imaginative and talented people in order to run at all (The folks at Bluepoint, Nixxes, and Panic Button come to mind). But if that’s all she wrote, you’re looking at a bread-and-butter port. There are many who hold the untouched port as the most ideal form of game preservation, and many more who don’t see the point of a fresh release of an older game if the developers don’t update anything, but the simple fact remains that basic ports allow more people to play more videogames and they’re an unavoidable part of the landscape.

IT’S A PORT IF: it shows up on a different platform from the original release, and barely anything has changed beyond what the new platform inherently offers to its games.

Enhanced Port

A game qualifies as an enhanced port in my mind if there has been little to no discernible graphical work done under a game’s hood since its original release, thereby qualifying it as a straight port if not for one or two clear and way-too-significant gameplay changes that have been implemented. Weirdly enough, this opens the door for re-releases to occur on the same platform as their source material, a practice for which the Kingdom Hearts franchise used to be infamous and something the Pokemon main series did with immense success right up until 2020, when it switched to a DLC Expansion strategy instead. The concept of an enhanced port definitely represents a curious semantic pocket of the industry, because while you can theoretically port a game to the platform it’s already on, without any noteworthy enhancements such an endeavour would be literally pointless.

Of course, most of the qualifiers for this category actually do cross over to new platforms, and as you might expect if you’ve invested in any of their recent consoles, Nintendo features heavily among them. The notoriously port-happy Big N greenlit an almost exhaustive catalogue of exports from the tragic Wii U to the hit-making Switch over its long life to give the a stranded titles a chance at sales, each packing little more than a resolution bump in the visuals department but almost always carrying a smattering of bullet points to set the new version apart.

For example, Hyrule Warriors Definitive Edition packs new character skins and integrates content from multiple previous versions of the game, New Super Mario Bros U Deluxe and DK Country Tropical Freeze add new characters and abilities, Super Mario 3D World + Bowser’s Fury adds, well, Bowser’s Fury, and Mario Kart 8 Deluxe fundamentally changes the flow of gameplay with more granular kart stats, tweaked balancing and an extra item slot per player (in addition to new characters). Older instances include the Gamecube release of Sonic Adventure 2 with an entire multiplayer mode in tow, the transformed controls and gameplay balance of Resident Evil 4‘s Wii edition and the enabling of the mythical “Stop n’ Swap” functionality in the Xbox 360 version of Banjo-Kazooie.

IT’S AN ENHANCED PORT IF: it basically looks / sounds the same, but substantial gameplay content has been added or even changed.

Remaster

For the sheer amount of use this label gets, you’d swear people would agree more on what it means, but thanks to marketing departments throwing it around flippantly over a decade ago like a shiny new toy, disagreement is still common to this day as to its actual function.

Based on a term used for decades in music production, the remaster ideally focuses on adding new textures – sometimes even models – within an existing graphical framework (oftentimes some parts of the original game remain untouched) in order to dress it up for a newer, more powerful platform. As a result, I am yet to see a remaster that doesn’t appear on a different platform from its original issue, which immediately distinguishes the category from the enhanced port. What’s more, prominent new gameplay features are not required – although they definitely can appear. In keeping with the musical origin of the term, new sound mixes are common companions to the visual re-skinning, though they are also not required.

Think Dark Souls Remastered, Skyrim Special Edition, and Final Fantasy X/X-2 Remaster on the humbler end of the change list (lots of new textures, some model adjustments, lighting changes), Xenoblade Chronicles Definitive Edition, Final Fantasy Type-0 HD, Okami HD, and Metroid Prime Remastered on the higher end (whole new HD models sprinkled in, obscenely high-resolution texture replacements, or even entirely new lightning systems), and Wind Waker/Twilight Princess/Skyward Sword‘s respective “HD” remasters / Final Fantasy XII: The Zodiac Age in the camp that plugs in new textures while also packing noticeable gameplay tweaks.

Crucially, a remaster rarely plays differently moment-to-moment from the last time it was released, aside from any added fluidity borne from a possible boosted frame rate. Put two assets side by side on different versions of the game and though one will look better, both will usually be in the same place and react the same way to the player’s input.

IT’S A REMASTER IF: it looks noticeably more technically up-to-date than the original, but almost every asset is still in the same place and functions the same.

Atlus-Tier Re-Release

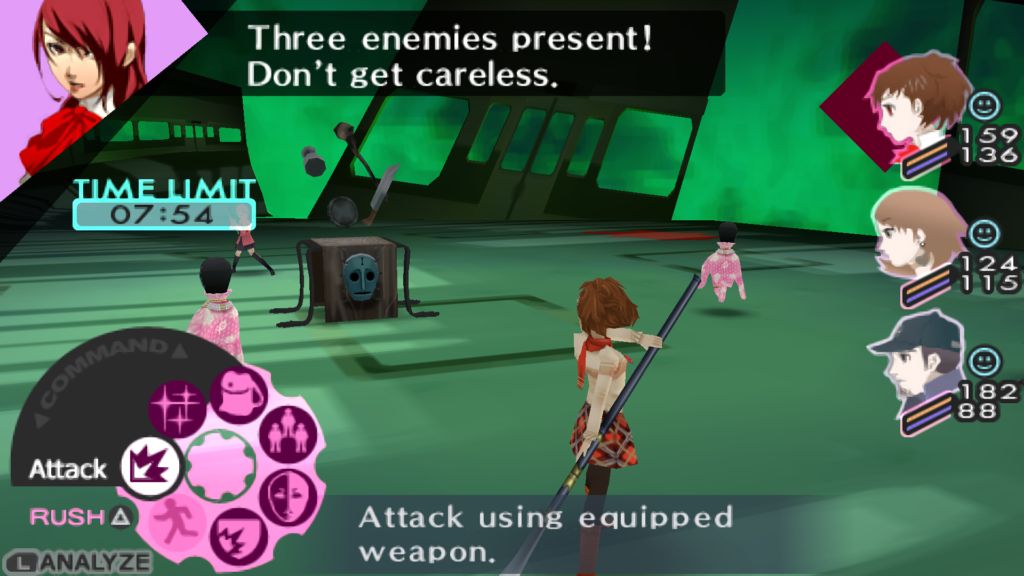

Yep, that’s right, the output from Atlus – specifically their Persona Team – deserves its own category right in the middle of the list. This category probably isn’t worth taking that seriously, but the original idea for this post stemmed from a conversation I had with a friend about Persona series re-releases and how difficult they are to properly categorise, so I feel I have to include it. No other prominent game developer puts so much effort – and time – into making sure an existing game takes on incredible new life without losing its identity, or even really looking all that different from its source at a glance.

Though the PSP re-release of Persona 2: Innocent Sin probably doesn’t qualify for this category – as it was more of an enhanced port – the sheer time afforded to the development teams behind each subsequent Persona re-release truly is unparalleled in this industry. After blowing away expectations for a re-release with Persona 3 FES on the PS2 in 2008, the company took 3-4 years between Persona 3 and Persona 3 Portable, then repeated the feat between Persona 4 and Persona 4 Golden, then again with Persona 5 and Persona 5 Royal. Each time the team set a new standard no other publisher seemed willing or able to match.

In fairness, if the Persona series wasn’t so highly-regarded it would be hard to imagine a world where releasing a game that looks halfway between a port and a remaster makes you any decent sum of money, especially when the new version often appears on the same platform as the original. But Atlus makes these games anyway, and so far they are knocking them out of the park, each time adding unruly hours to an already lengthy average playtime. With substantial additional time sinks of the gameplay and story variety iced with delicious presentation overhauls, these packages are acid trip director’s cuts bursting at the seams with treats for new and returning players alike.

Now if you were to try hard enough, you could probably try to fit some non-Persona games into this category, but that troublesome additional story content qualifier makes things tricky. You might say Tales of Vesperia counts if you ignore the Japan-only PS3 release, as on paper the multi-platform Definitive Edition ticks all the requisite boxes over the Xbox 360 original, but you’d be scraping the barrel there. Shin Megami Tensei V Vengeance, on the other hand, is a non-Persona game that ticks essentially all the boxes, but who publishes that game? Oh yeah, Atlus.

Persona 3 Reload is instead an entry in our next category.

IT’S AN ATLUS-TIER RE-RELEASE IF: it looks like an enhanced port most of the time, but has just enough new visual assets and way too much new story/gameplay/music content to qualify for that tier. If this sounds confusing, you can pretty much ignore this entire category anyway because only one publisher really uses it.

Remake

The only heading on this page that has been overused and misunderstood for longer than the remaster, a remake is actually quite easy to define at its heart: has the game been re-made? Has it been rebuilt, recreated “from the ground up” in order to merely resemble the original release?

If so, it’s a remake. These projects almost always set loftier technical goals than those implied by the humbler remaster, and indicate a titanic technical effort on the part of the developers bringing it to (renewed) life. Unlike everything I’ve covered so far, a project of this scale and ambition presupposes that it has been a decent amount of time since the original release – long enough for the source game to have been out of circulation and/or fashion for a while.

The aim of a remake is usually to recapture the “feel” of the original as closely as possible while using entirely new building blocks, often all the way down to the physics engine powering the flow of movement. This allows for varying degrees of stylistic freedom depending on how closely the new game is attempting to mirror the old, although the overwhelming majority of the original’s gameplay content will still be there essentially as players remember it.

Take the night-and-day differences from PS1 to PS4 inherent in Spyro Reignited Trilogy and Crash Bandicoot N.Sane Trilogy – both piloted by Toys For Bob. They represent a complete visual overhaul that hews closer to the “spiritual” line of remake, while Grezzo’s mightily impressive recreations of the two Nintendo 64 Zelda games on 3DS manage to inhabit the memories of playing on the N64 so effectively that it initially feels almost disappointing – until you see side-by-side comparisons and truly take in the tremendous differences in model quality, textural choices and even the positioning of physical geometry.

The same can be said for Intelligent Systems’ second bite at Paper Mario: The Thousand Year Door on Switch, which immediately reveals its status as a ground-up remake because the technical choices made within its modern visual mission statement necessitate a lower frame rate than the Gamecube original. The Last of Us and Shadow of the Colossus, meanwhile, each have the distinction of three distinct available versions: the original (in 2005 and 2013 respectively), a remastered release (2011 and 2014), and a full remake (2018 and 2022).

In the realm of 2D games – especially older ones – remakes are both more common and easier to distinguish than other forms of re-release, because the development cost difference between “remastering” pixel art assets in a discernible way (a la Square Enix’s modern releases of the first six Final Fantasy games) and just re-doing or outright replacing them with 3D models is traditionally negligible. Metroid Zero Mission, Star Ocean: The Second Story R, and Advance Wars 1+2: Re-Boot Camp represent three distinctly different visual approaches to 2D game remakes.

Remakes are also known for remixing, re-recording or otherwise rearranging audio, but that’s where the requirements stop. Most modern remakes are content achieving their mood-centric mission statement, only making gameplay or pacing changes where a well-known flaw or imbalance needs addressing. Or, in the case of the early 2000s remake of Resident Evil, just to mess with the player.

IT’S A REMAKE IF: it has been rebuilt as a new product from the ground up, albeit with extremely faithful visual resemblance to the source material. The telltale sign is often physical geometry in slightly different positions. Meaningful new gameplay content, however, is optional.

Reimagining

Still well under a decade old, the reimagining is understandably still trying to find its footing as a clearly-defined category of re-release, but its existence is critical to expectation management and our appreciation for the effort that goes into them. The undisputed flag-flyers for the reimagining are the modern versions of Resident Evil 2, 3 and 4, as well as the extremely misleadingly-named Final Fantasy VII Remake and its more sensible sequel Rebirth. The PS4 release of Ratchet & Clank from 2016 also counts, as do the multiplayer half of Conker: Live & Reloaded (the single-player component is more akin to a regular remake) and the surprising 2024 Switch treatment given to the 2005 DS and 2009 Wii games in the Another Code series.

The people behind these games take often-beloved source material and believe so strongly in updating the experience for a contemporary audience that the resulting product is essentially recognisable only by name, characters, setting and the most important of story beats. The flow and content of the story may be near-unrecognisable in places, or they could stay remarkably similar throughout – but the gameplay is different enough that it arguably could have anchored its own game without so much as a second glance from the public. To distinguish itself from a reboot, however, a reimagining still features just enough elements from the original that it can still share an exact name.

More homage than renewal, the creative advantages of a reimagining are uniquely tantalising, as it can exist alongside its source without needing to replace it. In theory this minimises the avenues for discontent and complaints among a fanbase – as long as the reimagined release is good – but we all know what the internet is like.

IT’S A REIMAGINING IF: it feels like an alternate take on the original, with new content often replacing (rather than adding to) old content. It’s still basically the same overall story, but how it plays is starkly different.

Reboot

The logical endpoint of the idea to capitalise on existing intellectual property, the reboot is unbeholden to just about all of the restrictions I’ve outlined so far. My favourite example has to be the most recent Tomb Raider trilogy, but there’s also the infamous DmC: Devil May Cry, the less infamous Infamous: Second Son, the ill-fated Advance Wars: Days of Ruin, the still-underrated Wolfenstein: The New Order, and plenty more. A reboot is functionally a sequel/prequel in every department that matters, except it lacks an explicit number in its title and doesn’t share explicit continuity with any other games in the franchise. Conceptually, a reboot allows a developer to explore ideas that may not have fit in with an existing franchise via a narrative blank slate while enjoying the built-in interest – and hopefully sales – of the series name attached to the project.

Such projects are naturally fraught with danger, however, as if fans feel like a previous continuity was left unfinished you face an uphill battle to earn their affection back. Look no further than the aforementioned DmC and Days of Ruin. One way to combat this is the so-called “soft reboot” – think the critically-adored 2018 PS4 game God of War – a nominal sequel or prequel in terms of story that completely overhauls just about everything else making it a videogame. As the costs of game development continue to rise and publishers look for safer ways to package their new releases, we might start to see more of these.

IT’S A REBOOT IF: the only thing it shares with the original is a title, a (rough) genre, and probably some characters. The rest could be anything. Technically this isn’t a type of re-release – rather a fresh start of sorts – but I really wanted to get to seven categories.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

And now to bring it all home with a good old chart: